Add description, images, menus and links to your mega menu

A column with no settings can be used as a spacer

Link to your collections, sales and even external links

Add up to five columns

Add description, images, menus and links to your mega menu

A column with no settings can be used as a spacer

Link to your collections, sales and even external links

Add up to five columns

When Art is Imitating Life: Bach and Coffee

May 31, 2018 3 min read

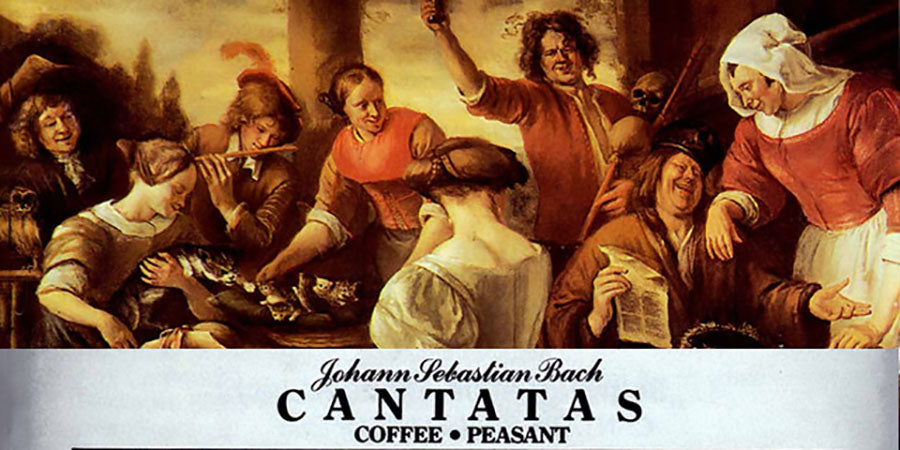

When Art is Imitating Life: Bach and Coffee

When Art Imitates Life: Bach's Coffee Cantata and the History of Coffee

Johann Sebastian Bach's Coffee Cantata is a humorous and insightful exploration of the early history of coffee in Europe. This delightful piece of music sheds light on how coffee was perceived and its cultural impact during the 18th century.

The Story Behind Bach's Coffee Cantata

The Coffee Cantata tells the story of a father, Schlendrian, who is determined to stop his daughter, Liesgen, from drinking coffee—a beverage considered unladylike and potentially harmful at the time. The setting is a coffeehouse, where Schlendrian attempts to dissuade Liesgen with warnings about coffee making her sick, ruining her beauty, and hindering her marriage prospects. Liesgen, however, remains unconvinced and passionately defends her love for coffee, describing it as "sweeter than a thousand kisses" and "milder than muscatel wine."

In a surprising twist, the cantata concludes with Schlendrian conceding and allowing Liesgen to drink coffee. This ending reflects Bach's awareness of coffee's growing popularity and challenges the prevailing negative views of the beverage.

The Historical Context of Coffee

Bach's Coffee Cantata offers a fascinating glimpse into coffee's history. In the 18th century, coffee was often viewed with suspicion and considered unhealthy. Despite these beliefs, coffee gradually became one of the world's most beloved drinks. The cantata highlights how art can challenge social norms and reflect changing attitudes.

Musical Excellence and Humor

Beyond its historical significance, the Coffee Cantata is a well-crafted musical piece. The witty lyrics and lively music make it a joy to listen to, providing a unique perspective on coffee's cultural journey. Bach's humorous approach underscores the absurdity of the period's coffee-related fears while celebrating the beverage's undeniable appeal.

Bach's Contemporaries and Their Views on Coffee

During Bach's time, many believed coffee had both beneficial and detrimental effects. Some doctors claimed it alleviated constipation, reduced swelling, and even cured the bubonic plague. However, rumors also suggested coffee could "unman" its male drinkers. The cantata fits into the broader context of coffee humor, which included satirical works about coffeehouses as places where men avoided their domestic responsibilities.

Coffee and Social Concerns

Caffeine, identified as coffee's active ingredient only in the early 1830s, was known for its stimulating properties. This led to concerns among politicians and officials about its impact on public behavior. Coffeehouses were seen as places of idleness, potentially undermining productivity. Bach’s character, Schlendrian, whose name translates to "lazy," reflects these societal anxieties.

Leipzig's Coffee Culture

Bach's cantata also pokes fun at Leipzig, where officials had tried to regulate coffeehouse hours and discouraged coffee consumption among the youth. Despite fears that coffee could lead to moral decline, it was also believed to have medicinal properties, inspire revolutions, and stimulate both mind and body.

Bach's Coffee Cantata is a delightful blend of humor, music, and social commentary. It offers an entertaining yet insightful look at the history of coffee and its cultural significance. For those interested in the intersection of art and history, or simply looking for a good laugh, Bach's Coffee Cantata is a must-listen.

If you want to delve deeper into the history of coffee or enjoy a lighthearted musical piece, Johann Sebastian Bach's Coffee Cantata is an excellent choice. This captivating work provides a unique window into the past, illustrating how coffee evolved from a controversial drink to an everyday staple.

How to order coffee around the world

What are the world's top coffee consuming nations?

Subscribe

Sign up to get the latest on sales, new releases and more …